Why your website strategy is missing the mark.

And how to fix it using our 1-3-5-7-9 formula for successful social venture sites

KEVIN L. BROWN

Websites are often the graveyard where social venture brands die.

A website is the most critical communications channel for any nonprofit or social enterprise brand. But it’s commonly a disastrous afterthought. Web strategy can feel too complicated. Good design and content seem expensive. Or leaders say there’s no time or team.

We had an early client with a history of impact and a unique racial equality mission, but a horrible website strategy. They were a nonprofit that ran a summer camp for less privileged kids. Paid registrations fueled their earned revenue model. But the naive web firm had slapped donate and volunteer buttons everywhere. That’s what nonprofits are supposed to do, right? Unfortunately, the site didn’t encourage visitors to sign up for camp — the vital business goal. And millions of dollars were lost over time.

Google shows 4.2 billion search results for “nonprofit website.” Indeed, every organization we’ve served has and needs one. We could argue some limp along without a theory of change or positioning strategy. In terms of marketing communications — some use email, others maybe social media. But the website is unmatched in universal importance.

Even if only once, almost every priority audience will visit your site — from individual donors to government partners to potential staff. So, you can’t drive income and impact without it. We could even argue the website is the ultimate expression of a brand strategy.

So why are nonprofit and social enterprise websites notoriously bad? Thanks to out-of-the-box solutions, building a site has become remarkably cheap from a design and technology standpoint. You can find talented freelancers anywhere and activate them quickly via services like Catchafire and Upwork. It seems the strategic connective tissue is what’s really missing.

“A website strategy is a plan of action that directs the content, layout, and funnel on your website. It considers your business objectives and then outlines the ways your website can align with those plans to actively help you reach your goals.”

RAUBI MARIE PERILLI

The 1-3-5-7-9 formula.

Unfortunately there’s no shared format or ubiquitous template to borrow for web strategy. So here’s our formula for growth-stage social ventures. Remember 1-3-5-7-9 for the elements that matter most: one call-to-action, three audience goals, five sitemap pages, seven homepage sections, and a $9,000 average budget.

1 Call-to-action

Your website strategy starts by determining the most critical, one call-to-action on the site. Essentially: if you boil it all down, what is the site for in the first place?

Here’s a thought experiment to help you courageously focus. Imagine your entire website was just one page with one logo, one photo, one paragraph, and one button. What would the button link be? This singular transaction goal or conversion will generate most of your brand’s income or impact. You’re trying to identify the one user journey you must facilitate most often.

For a lot of nonprofits or charities, this most critical call-to-action will be Donate. With Justice Defenders — it’s a big red button in the navigation that stays fixed as you scroll, the first button you see on the homepage hero, and even repeated in the bottom picture as Join the Defenders.

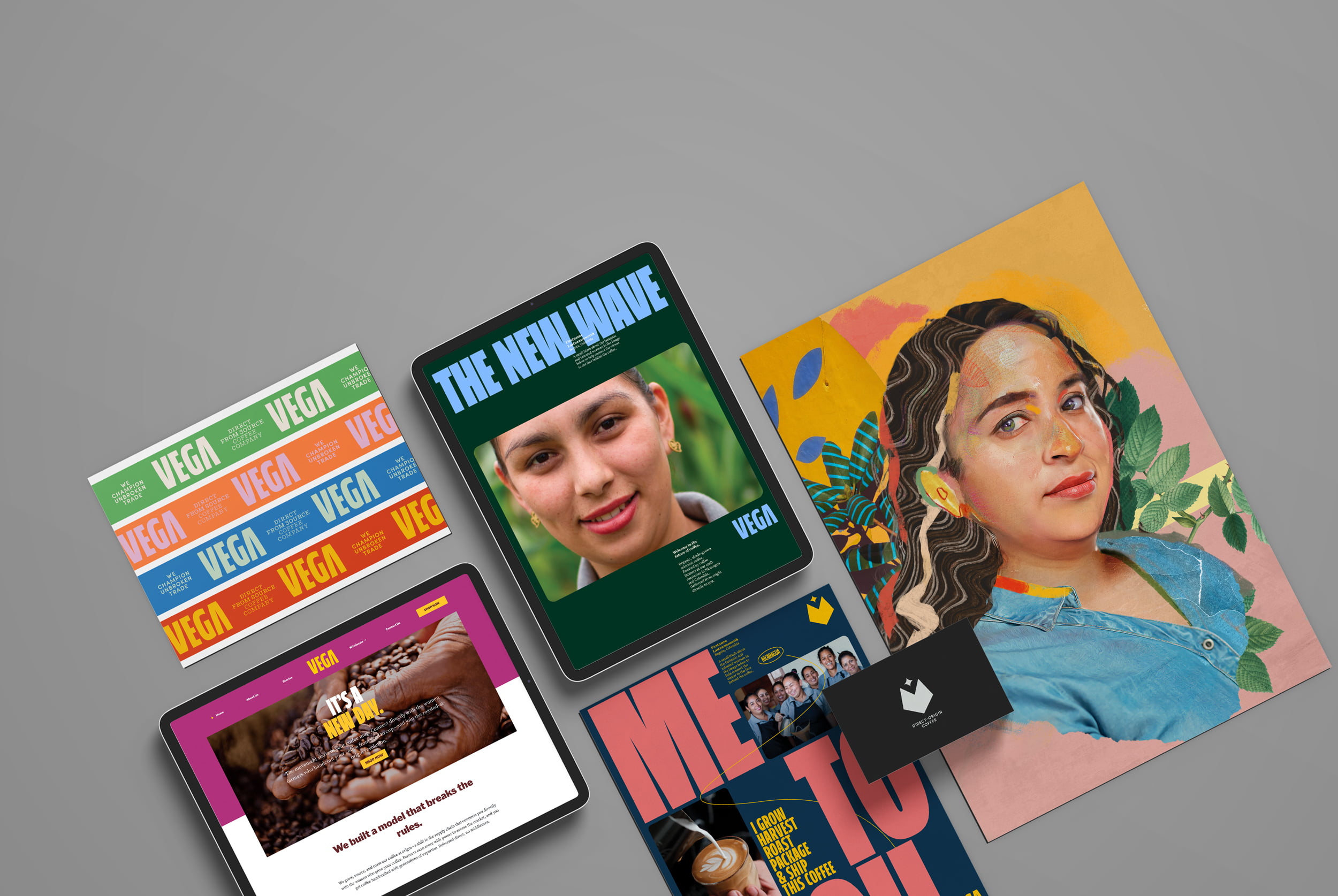

For social enterprises that sell online, it may be Shop Now. Just like Vega Coffee — you can’t miss the button as you navigate the site. But it can be anything. For example, our client JUST is repeatedly inviting women to sign up and Join the community.

The point is to identify the main desired conversion and do everything to get people into that sales funnel. A confused mind always says “no”. So don’t try to convert too many people into too many paths simultaneously.

A final note about your call-to-action and sales funnel. Don’t forget what happens once you convert a web visitor into clicking. With so much focus on getting audiences to your most important page, it’s easy to forget the steps to be taken afterward. All too often, donation pages aren’t optimized. The confirmation message or email receipt is broken when people give or buy. These errors are brand and income killers. So yes, bring the horse to water. But also ensure it can drink.

“It’s much easier to double your business by doubling your conversion rate than by doubling your traffic.”

JEFF EISENBERG

3 Audience goals

The obsessive focus on a singular call-to-action is an excellent start. But of course, websites need to serve more than just one purpose. Once the strategy is complete, you move into content development and actual page design — with lots of little decisions to come around organization and presentation of information. So, you must carry over a critical piece of your positioning strategy: priority audiences.

You should already know — well before the website work — the top three audiences you’re trying to reach with your brand. For example, you might target high-net-worth donors, bilateral funders, and ministry officials. And you should know their pains and gains. Therefore, your website strategy should serve three audience goals: one macro goal for each target.

Here’s an example from our recent rebrand and website launch with Vega Coffee. Their top three priority audiences and goals for each were:

1. Discerning, savvy customer: easily find and navigate to “shop” in order to select desired coffee and frequency, then complete purchase.

2. University foodservice decision-maker: understand the basics of the Vega model to reinforce the price/quality brand promise.

3. Brand ingredient buyer: perceive Vega as an established brand with clout that can help improve their own brand’s perception.

Listing a goal for each audience is a lot easier than accomplishing said goal. That’s the art and science of positioning and marketing communications. For example, what if a goal for industry influencers is showcasing your thought leadership. Do you start a blog on the site? Do you publish a white paper on the homepage? Or instead, link out to all the podcasts you’re featured on?

There’s no exact recipe here, but you must at least ensure each audience is being considered. Then you can make deliberate decisions with your sitemap and homepage sections below.

5 Sitemap pages

A sitemap is simply a list of pages of a website. You’ll see the sitemap reflected in your website’s navigation. e.g., the menu options at the top. The website developer will create an XML file that helps search engines index all of your website’s content. But what we’re talking about here is a tool used in planning out the website strategy and architecture — not a technical feature.

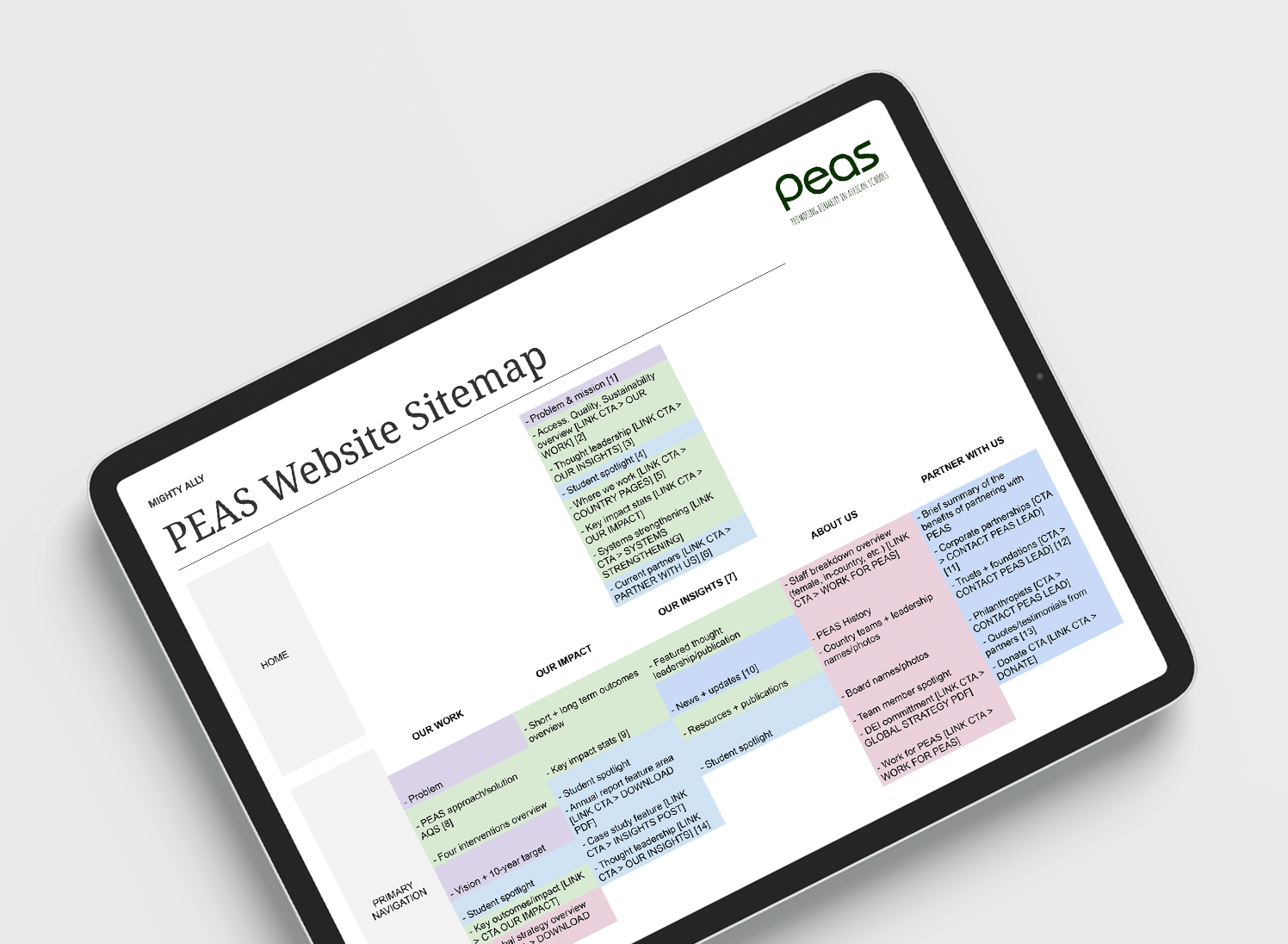

Sitemaps can look like flow charts or Google Sheets to show layers of pages. Although, just like a homepage wireframe, nothing more than pen and paper will suffice to sketch out the website’s organization.

We recommend a primary navigation of five sitemap pages. Give or take a page, including your main conversion page like Contact Us or Donate. Because, most growth-stage social ventures don’t have significant, enterprise-level websites requiring dozens of pages. Especially considering each of your five subpages can contain upwards of seven sections just like your homepage. That’s already 35 sections of content to scroll through!

If you absolutely need more than five main pages, include the less critical ones in the smaller secondary navigation above the main menu. Or as drop-down menu items called subpages. But stop at five subpages on top of your five main pages for 10 total pages, max. Because an average website visitor will only spend 1.5 minutes on your site. So giving them too many pages is just overwhelming visually. And they just can’t digest it all. Better would be linking to detailed PDFs. Or converting the user into contacting you, so you can share in-depth during a conversation. Not trying to squeeze everything you have to say into the site.

The big exception here is social enterprises with ecommerce on the site and multiple products to sell. But most social ventures only need to explain their work and generate donations or inquiries.

Look at the sitemap for Mighty Ally. Our own site has just five subpages: Expertise, Insights, Impact, About, and Partner with Us. Then of course pages like Insights link further into blogs and Impact connects to individual case studies. But we’re not trying to cram all of those options into the navigation. Keep it clean.

Bonus points if your sitemap contains search engine optimization strategies like title tags, keyword priorities, and meta descriptions for each page. That information will be needed by the web developer when coding. So, might as well include these important SEO details while sketching out each page and the content within.

As you can see in our recent website strategy work with PEAS, the sitemap is nothing fancy. It’s just listing out all the pages on the site. Then roughly detailing the type of content that will go into each page. Some web designers will prefer a full wireframe for each page. The best ones will want the creative freedom to take this sitemap and bring the page to life.

7 Homepage sections

Stating the obvious: your homepage is the essential front door of your brand. So spend more of your website strategy time here, because most visitors will see your homepage plus maybe 1–2 other pages. That’s it. If you don’t hook them right away and give them a clear path to proceed, you’ve lost the game.

A wireframe details the layout and flow of your website information. Also known as a page schematic or screen blueprint, wires are a visual guide that shows the skeleton of a site. And we recommend seven homepage sections in your wireframe. Any less, and you’ll likely not be able to tell a complete story on your homepage while linking off to your important subpage content. Any more, and your users will be endlessly scrolling.

Our recommended homepage wireframe is based on user experience studies and story arc best practices. Like our tools in the messaging and storytelling guide, there’s a proven flow for how people receive and process information. So whether you write out your homepage wireframe in a text document or use a visual format, here are the standard seven sections:

1. Header

Lead with the problem you’re solving and who you’re serving. This hero area hooks the visitor and sets the stage for what’s to come.

2. Brand promise

Explain the value proposition of your product or service. This text can be your mission or reason from the theory of change.

3. About

Now, let the visitor ‘meet the guide’ behind the work. Share a bit about your organization so they’ll feel connected to the cause.

4. The model

Here you’ll reassure the visitor that the guide (you) has a plan or proven process. This piece can be your main 3–4 interventions.

5. Impact

It’s time to brag. At this point, you showcase your success to date. Impact stats are ideal — outcomes are better than outputs.

6. Authority

If the impact data hasn’t convinced the visitor to convert, use testimonials and/or logos here to give social proof.

7. Footer

Put everything else in this bottom section. Like the email signup (unless it’s your main call-to-action!), social icons, and other content not important enough for the main nav.

These sections are modular and can shift up or down — slightly — to meet your model. But modify at your own risk, as the story arc can easily break down. To see this homepage structure in action, again check out the examples of Mighty Ally and Justice Defenders.

Most homepage sections will have a link to learn more. So resist the urge to pack it all into the homepage. Instead, use the sitemap to plan for subpages that go into more detail.

Your homepage wireframe does not have to be complicated. Sure, there are great tech tools like the basic Balsamiq to the complex Marvel if you want to geek out. But you can effectively sketch out a homepage using nothing more than a notepad or whiteboard and the seven sections above. Again, it’s the thinking that matters, not creating something flashy.

$9k Average budget

How much does a website cost? We get that question all the time. Well, how much does a car or house cost? The answer, of course: it depends. You can get one for cheap, expensive, and in between in all three cases. And the quality/features will vary accordingly.

For this reason, finish your website strategy process by determining your budget. Because, all the decisions above need to be grounded in what you can actually afford. And budget is the main question a web development firm will want to know.

Gone are the days of custom websites that cost more than $100k. High-end sites from quality web shops run $20k–$40k. Though sometimes as little as $2,500 for a very basic website from a freelancer in a platform like Squarespace. So social ventures can get a decent website designed and developed for a $9,000 USD average budget.

But you get what you pay for — code quality, design touches, and custom features only add to that average estimate.

It’s key to note: this budget range assumes you have your theory of change, positioning, branding, website strategy, and content in place. Content is key: you can’t continue past this web strategy process without the right messaging and images locked down. Plus, a marketing communications plan to drive traffic to said site.

All this brand strategy work (like what we do at Mighty Ally) takes months and is truly what makes or breaks a good site. Because, remember: a website is but the reflection of your brand — just like a speech you give or a funding application you submit.

In short, web shops are experts in just that: websites. Not strategy. So, don’t conflate the two. The budget levels above apply to the tactical side of website design, coding, and launch alone.

On the newly-launched brand and website for Vega Coffee, you can see the 1-3-5-7-9 website strategy come to life. One call-to-action: shop. Three priority audiences considered, each with a goal. Five sitemap pages with seven clear homepage sections. All at a budget any growth-stage social venture could afford.

Pulling it all together: the website strategy brief.

Congratulations. You now have the most critical elements of a website strategy. So, where does this strategy go? And how do you act on it?

Meet the website strategy brief. A basic document that houses everything we’ve covered, along with a few extras. The tool that rallies the brainstorming, ensures leaders are on the same page with decisions, and allows a seamless handoff to website developers. A living and breathing reference point throughout the website design and coding to come.

Your web strategy brief should contain the 1-3-5-7-9 formula above, at the very least. It can also include some additional strategic thinking and technical details too. Like these optional sections:

RWMC

Use the four helpful lists to audit your existing website. Gather the team and document what’s Right, Wrong, Missing, and Confused with it. This retrospective on the current state of affairs will be invaluable in developing the new site.

Landscape analysis

Don’t hesitate to look around at the competitors and collaborators. Reference those identified during positioning to see what others are doing on the web. You can use the RWMC lists to capture what you like and dislike about other organizations’ websites.

Analytics review

Take advantage of tools like Google Analytics to analyze performance of the current site. Look to see where users come from in the world, what sources drove them there, the most popular pages they visit, the devices they’re using, and where they drop off.

Content requirements

This brief is your chance to identify any new copy or multimedia needed beyond your current content. Maybe you want to add a blog — then it’s time to write. You might have sketched a big video on your homepage — do you have one? You get the point.

Technical requirements

You must consider and document all the functional needs of the new site. For instance, donation platforms, CRM integrations, email signup code, ecommerce capabilities, or custom features such as searchable databases.

With the website strategy brief complete, it’s off to the races! Time to hand it off to the website design and development team — whether that’s internal or a third-party firm.

Final thoughts: an iterative process.

You’ll hear us often say: you don’t just develop a brand, set it, and forget it. Brand management means just that — ongoing attention and iteration. Your theory of change and positioning strategy will need constant pressure testing as conditions on the ground change. Your messaging and storytelling platform will evolve. As will your marcom efforts and website.

Using the Japanese philosophy of Kaizen, focus on continuous improvement of your new site using small steps. Because there’s never a final version. “You can always make improvements,” says Dmitry Fadeyev in Smashing Magazine. “This is because a website isn’t a magazine that you print and sell. A website sits on your server… you can introduce gradual improvements and updates to make your website more effective in serving its function.”

When in doubt about how the new site performs, use a real-world usability test recommended by donation platform QGiv. The idea here is that people may only give your site a few seconds before losing attention. So this test is a way to measure your website’s engagement. Recruit a volunteer who is unfamiliar with your website. Set a timer and pull up your site. After 30 seconds, ask them to tell you what your organization is about and what action they should take. If they don’t know, it’s time to keep tweaking.

Go forth and launch. Then study the analytics, optimize, lather, rinse, repeat. Good luck.

“A bad website is like a grumpy salesperson.”

JAKOB NIELSEN

Read more articles

Ready to get fundable and findable?

We engage three ways: consulting, training, and field building.