The best story wins. Here’s how to write one.

A simple framework for feature story writing

It’s not about the best idea or product or program or leader. It’s organizations with the ability to tell good stories that rise to the top.

This truth, explained well by the Collaborative Fund, applies to any field. Especially in the social sector, where millions of nonprofits and social enterprises are doing similar — but complex — things.

Look at some of the biggest names and brightest stars in the space. Last Mile Health. One Acre Fund. Water.org. Educate Girls. Each has raised tens of millions in funding and won all sorts of awards. But their models aren’t that different from countless others.

So what is the difference? They tell great stories.

Tesla isn’t worth 7x GM and Ford combined because it’s a good business. No, it’s because Elon Musk is a master at grabbing people’s attention, from investors to Twitter followers.

Storytelling through public speaking is both a gift and a practice. But in reality, most leaders aren’t on stage often.

Video is an incredible storytelling tool. But it takes a lot of time and money — things changemakers typically don’t have a lot of.

So what’s the best (affordable) way to tell a good story? Writing. Which is where we see many clients get stuck.

Great ideas, effective products and programs, impactful work — but limited ability to put the words on a page. Blogs going stale. Email newsletters drying up. Engagement waning.

So if you’re consistently staring at a blank Google Doc with writer’s block, read on for help.

“The best story wins. This drives you crazy if you assume the world is swayed by facts and objectivity. But we live in a world where people are bored, impatient, emotional, and need complicated things distilled into easy-to-grasp scenes.”

MORGAN HOUSEL, COLLABORATIVE FUND

Meet the feature story.

A feature story is an article that goes beyond the facts to weave in a fleshed-out narrative and tell a compelling story. It differs from a hard news piece because it offers an in-depth look at a particular subject, current event, or location to audiences.

A good feature provides a new angle. There’s creative use of language. It’s more detailed and often longer. It can be educational or entertaining, arousing emotions. It combines facts and opinions. It does not expire. And it should contain depth of characters and/or issue.

One study found that feature stories increase reading by 520% and readers by 300%. In another piece of research, Reuters Institute says features go viral more often.

Feature story structure.

A solid structure helps readers navigate, makes writing quality better, and saves time drafting/editing.

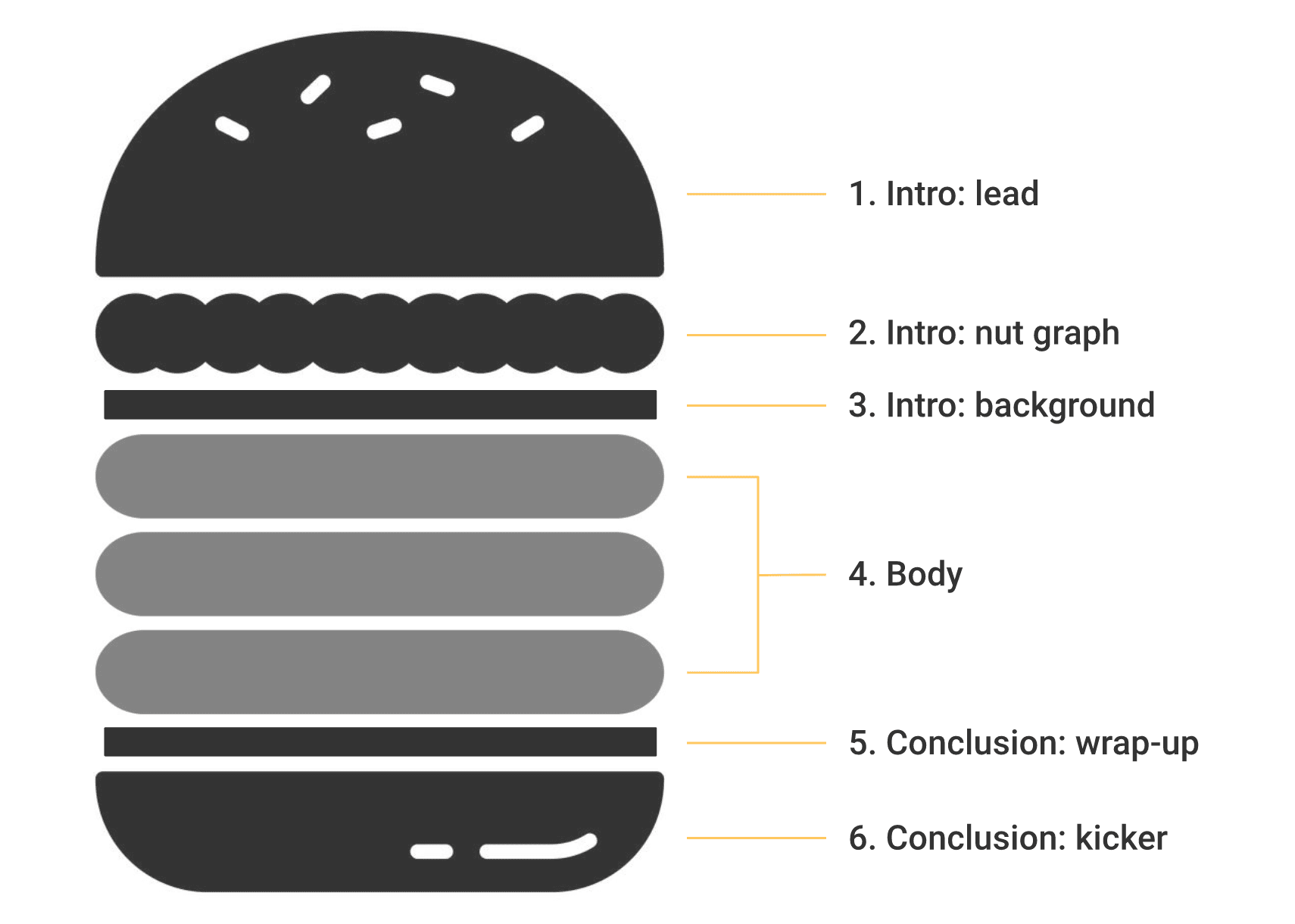

Just like your teacher taught in school, good stories have a beginning, middle, and end. Call this your intro, body, and conclusion. But each of these sections has its own pieces — six in total. Think of it like a hamburger, which we’ll unpack now.

1. Intro: lead

The lead’s job is to pull readers into the piece. The best way to do that is to write a lead that’s concrete, creative, and provocative.

There are several ways to accomplish this:

-

Punch — a short, snappy sentence as a paragraph by itself

-

Anecdotal — a specific story that illustrates the main point

-

Descriptive — concentrates on the five senses, showing readers what the event or person looked and felt like

-

Pun — to surprise and entertain the reader

-

Allusion — plays to the reader’s knowledge of literature, history, or mythology

“The most important sentence in any article is the first one. If it doesn’t induce the reader to proceed to the second sentence, your article is dead.”

WILLIAM ZINSSER, WRITER

2. Intro: nut graph

The nut graph explains the lead’s connection to the rest of the story. It reveals your destination, or the essential theme of the story. And it convinces readers to come along for the ride. How to write a nut graph:

-

Tell ’em what you’re going to tell ’em

-

Summarize your story angle in one sentence

-

Make a promise to your readers

-

Keep it short (two sentences max)

“I like the nut graph. Readers need a frame around the picture. But sometimes the nut graph sticks out like a pig going through a snake. It doesn’t have to be a paragraph. It can be one elegant line that foreshadows the rest of the story.”

JACQUI BANASZYNSKI, JOURNALIST

3. Intro: background

Readers might need some of these elements to fully understand your story:

-

A definition

-

Short description of a key concept

-

One-paragraph history of the subject

-

Additional facts or details that give context to the story

“Always grab the reader by the throat in the first paragraph. Sink your thumbs into his windpipe in the second and hold him against the wall until the tag line.”

PAUL O’NEIL, TIME MAGAZINE

4. Body

In the body, you build out the story into clear, logical parts. To help readers find what they’re looking for, label the parts with subheads.

The body includes one to three parts in which you explore the subject in more detail. If the nut graph is where you tell readers what you’re going to tell them, the body is where you actually tell them.

How to write your body using LATCH:

-

Location — move geographically, e.g. country to country

-

Alphabet — organize from A to Z

-

Theme — tackle your topic categorically

-

Chronology — progress from beginning to middle to end

-

Hierarchy — structure from most important to least

“When we read, we start at the beginning and continue until we reach the end. When we write, we start in the middle and fight our way out.”

VICKIE KARP, THE NEW YORKER

5. Wrap-up

In the wrap-up, you call readers to action or summarize the key message. The wrap-up is designed to make your point; the kicker, to make your point memorable. The best conclusions summarize then illustrate your key point.

How to write a wrap up:

-

Tell ‘em what you’ve told ‘em

-

Simply copy and paste the nut graph, then massage

The tone of the wrap-up is, “Now that I’ve given you all this information, you can only agree with me that [key point].”

“I always know the ending; that’s where I start.”

TONI MORRISON, NOBEL PRIZE LAUREATE

6. Conclusion: kicker

First impressions are important. But last impressions matter too. If you use your most intriguing material for your lead, put your second-best in the kicker.

Here’s a helpful exercise, recommended by Roy Peter Clark, Poynter Institute senior scholar: After you write your story, try switching the lead and the kicker. Does it work?

How to write a kicker:

-

Choose a telling detail for the end of the piece, which should reveal new meaning about the topic even as you close

-

A quotation is the most common approach for a feature-style kicker

-

Or provoke a question in the reader’s mind so she keeps thinking about your story long after she’s finished the last paragraph

“While we obsess about beginnings, we often don’t spend enough time sculpting our endings, or kickers, and that’s too bad. Endings are our last word to the reader, and often what readers remember most.”

MICHELLE NIJHUIS, JOURNALIST

Writing style best practices.

Now that you’ve got the basics of a feature story, here are some extra tips on improving your writing style. Style matters because it increases readability, establishes consistency, and improves brand perception.

Know why you’re writing

You must have a clear idea of what you want to say in order to communicate it efficiently. You need the facts in hand. And also to know what effect you want to have. Do you want to inform, sell, persuade, alarm, reassure, or what?

Do your research

Feature stories need more than straight facts and sensory details — they need evidence. Quotes, anecdotes, and interviews are all useful when gathering information. Hearing the viewpoints of witnesses or anyone else who can fill in gaps will help you craft a more vivid and interesting story.

Create an outline quickly

Use the hamburger structure as an outline. And set a timer for one hour to get all your notes and ideas on paper. Don’t worry about complete sentences yet. Notes in the right place will help you spot gaps and give you confidence to begin the real writing.

Craft a compelling headline

Feature stories rely on a writer’s ability to maintain a reader’s attention throughout an entire piece. But one of the harder parts is getting them interested enough to read the story in the first place. Your headline needs to pack a punch or pose a question readers will want your story to answer.

Get short

Use shorter paragraphs, shorter sentences. Even use fragments or begin sentences with conjunctions every now and then. Just don’t overuse. 3–5 sentences per paragraph (sometimes just 1–2). Route all content through the Hemingway Editor to find “hard to read” sentences and drop the grade level to nine, max.

Keep it simple

The clearest English sentence has a subject, a verb, and an object, with one extra subordinate clause at most. In other words, a sentence conveys one idea only with possibly one related point.

Ask “so what?”

Ask “so what” or “why?” five times to get to the root of why a piece of content matters. Always speak to the “so what?” and not just the “what.” In other words, don’t just state the facts. State why the facts matter.

Rely on verbs

Use verbs vs. nouns when you can. Strong active verbs are efficient and effective. Use the passive voice with caution, as it often simply takes more words while clouding meaning.

Scan for redundancies

As in, don’t use the word “fight” multiple times in one paragraph, even if spread out among different sentences. Use a thesaurus. Also, never place two direct quotes consecutively. Paraphrase in between quotes to bridge direct words.

Read, a lot

There’s a saying: “writers are readers.” Humans are built for input. So what we put into our minds likely comes out in our writing. When you read often, you’re more exposed to raw talent in others’ writing. This is a valuable experience to grow your craft.

Story and writing resources.

Want to dig in more? Here are some additional resources:

5 Tips for Writing a Captivating Feature Article

Wylie Communications blog: story structure

NPR Training: A good lead is everything — here’s how to write one

Read more articles

Ready to get fundable and findable?

We engage three ways: consulting, training, and field building.